The Top 25 Mistakes of COVID Mismanagement

Note: this article will be updated as more failures get highlighted by subscribers

There have been 3 million deaths so far and tens of millions of people with long COVID. As I explained last week, we could have had a few thousands instead.

We need to learn the lessons so that these widespread governmental failures don’t happen again. Here are the top 25 mistakes of COVID management I see so far, from least important to most.

25. Infection Parties

If people had wanted, they should have been able to proactively get infected with COVID and then remain isolated in a hotel or other facility until they test negative. It’s a contentious idea, but those against it don’t think in terms of costs and benefits.

If people want to get infected, why not let them? What do we care, as long as they don’t infect us?

The financial cost is low: the hotel stays for isolations and medical treatment for those who fall ill. A participation fee could have covered a substantial share of the cost, if not all—and helped hotels, which sorely needed the business during the pandemic.

This voluntarily infection could have been done in a safe way:

We could allow only young people to participate, for whom the fatality rate might be ~0.1% to 0.01%. That’s 10 to 100 times lower than for older people.

We could have controlled the viral dose, which would have reduced the fatality rate even further. As Robin Hanson said, many studies have found big effects of an initial virus dose, suggesting that tightly controlled infection could reduce the fatality rate between 3 and 30 times.

The benefit of voluntary infections, meanwhile, would have been huge: Those infected could have had a passport letting them off the hook of lockdowns. They would have been more free and helped the economy by living their near-normal lives.

But, more importantly, it might have added a strong element to COVID debates. “Don’t want to wear a mask? Don’t want to respect the lockdown? Think this is like the flu? Here’s your ticket to the infection party!”

Plus, I think only a few people would have done it. It’s a concept that might sound compelling to some in theory until they saw news of a 20 year-old girl who died in one of these infection parties.

24. Immunity Passports

The point of an infection party is to be free afterwards. The participants would have needed immunization passports to prove their immunity.

The passports would have come in handy for the tens of millions who survived COVID but still had to respect lockdowns. And, obviously, we wouldn’t be still debating vaccine passports.

Here are the concerns about passports:

It’s problematic for data privacy, since authorities would require storing personal data.

Except the government already knows *everything* about you. That’s how they know how to make you pay taxes.

This is sensitive healthcare data that would have to be shared with people.

Who has a terminal illness? That’s the type of sensitive healthcare data. Who got vaccinated is a source of social media gossip.

It discriminates against those who don’t want to give their data or aren’t vaccinated yet.

That’s very much the point. If you don’t want the freedom that comes with immunity passports, why should others pay for that? And if you aren’t vaccinated yet, you are at risk of spreading the virus. Why should you be able to roam free?

It’s impossible to pay a person to checks these passports at the door of any building or gathering.

Except we do it with temperature and PCR test results, and bouncers at nightclubs have done it for decades. With much more sensitive personal data from ID cards, by the way.

We should have had immunity passports for months now.

23. Not Knowing Who to Trust

In some places, like the US at the federal level, we didn’t pay attention to experts. In Sweden, meanwhile, the government handed the management of the pandemic over to experts and followed up with too little oversight—and the result was failure.

Meanwhile, on social media—which impacts public opinion, which then becomes policy—platforms were frantically trying to figure out who is right, who is wrong, who is dangerous, and whom to block.

I saw this firsthand. Many people read my articles and could judge by themselves their validity. But others couldn’t, and were bothered by my lack of formal credentials. When people have a hard time thinking for themselves, they logically turn to experts. The hordes that attacked me after the first articles calmed down after I published a list of endorsements. But no expert is perfect, and many disagreed with each other during the pandemic. So how can we know whom to trust?

I will write a full article about trust soon. It’s at the core of many social failures. We need better mechanisms for the 21st Century.

22. Underestimating People’s Willingness to Do the Right Thing

In March 2020, the UK delayed its lockdown a crucial week, resulting in thousands of unnecessary deaths. Why? Because they feared they couldn’t convince people of the necessity of lockdowns. Policymakers thought people wouldn’t respect the lockdowns.

I remember my despair debating a member of the UK’s SAGE group on TV that week. It would later be revealed that the false ideas about people’s unwillingness to abide by the lockdowns came from unnamed behavioral psychologists advising the government.

I hate it when we underestimate people. When you ask people to make a sacrifice for the common good, and you explain clearly why they need to do it, people respond. Humans like doing what’s right, even if it’s hard.

Theories about human selfishness also often underestimate the ability of good leaders to stir the public opinion in the right direction. The Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Ardern, showed how it’s done with her famous “team of five million” communication.

21. Lying to the Public

Government officials—Fauci included—told us masks were useless for normal people. It was a lie, designed to reserve the masks for healthcare workers.

We should treat humans like adults and, as much as we can, always say the truth. Otherwise, people learn not to trust those who lie. How are you going to trust leaders when they later reverse their advice? When they tell you a vaccine is safe?

20. PCR Test Management

The US CDC inherited from the WHO PCR tests that worked. The CDC tried to reinvent the tests, failed, and forbade others to make them right.

Back in February and March 2020, the US was doing so well. It had so few cases! Maybe it helped that the country was only testing those coming back from China, because there weren’t enough PCR tests to test more people. And those available were faulty.

Not only that, but the U.S. also prevented other labs from making their own tests—until one courageous team got into a legal grey area, made its own tests, and started finding cases.

In a situation like this, when every minute counts, something is already proven to work, you’re not up to the task of fixing anything, and other qualified people want to help, just let them help.

19 . Letting States Fend for Themselves

Conversely, there are some decisions that governments should have owned. The main one is centralizing crisis management.

Here, the US is joined by other COVID success stories like Russia or Brazil. All three decided they weren’t going to do anything at the federal level, letting their states manage the pandemic.

Their states, obviously, had zero epidemiological management experience, and couldn’t do the job. They also started competing for things like personal protective equipment and ventilators.

They also didn’t dare to do what they had to do to protect people: close borders with other states.

In an emergency, you want a strong central government to coordinate everything and everybody. Even EU countries did this well. They fenced off different internal regions to stop the virus. But then they made the same mistake with other EU countries: because the EU didn’t weigh in, they were hesitant to close borders with each other, and reopened the borders way too early.

18. Forgetting that Good Fences Make Good Neighbors

It took ages for countries to close borders. And when the closings worked to contain the virus, they opened the borders back up!

Hawaii and Canada’s Atlantic Provinces didn’t care. They closed borders with their neighbors, kept them closed throughout, and largely avoided local epidemics.

Since then, most countries have erected aggressive fences. That doesn’t mean they are proper. A PCR test taken three days before boarding a plane is close to worthless. In most countries that do have some type of fence, such a test is the only measure they have to screen against passengers potentially bringing in the virus.

17. Storytelling Against Reality

Politicians are used to storytelling their way to anything: it’s easy to sell something when the consequences take years to appear, and even then, it’s not clear what caused those consequences.

That doesn’t work when the consequences appear in a matter of days or weeks and are counted in numbers of collapsed hospitals and piles of dead bodies.

Some still tried. Iran was the innovator here, until political and religious leaders starteddyingindroves. Trump and Bolsonaro, Brazil’s president, both claimed the virus didn’t exist, didn’t matter, and would be resolved quickly. Together, the official COVID death toll from those two countries adds up to 1 million —a third of all the world’s COVID deaths with 7% of the global population.

The best example of fairy tale-telling is Tanzania’s president: a vehement coronavirus denier, he died, you guessed it, of COVID.

16. Not Adapting to Lower Income Areas

Lower income areas had it much worse than high income areas:

Their jobs required them to work outside of home. They couldn’t be shielded from COVID like knowledge workers working remotely.

Because they have less of a voice, employers didn’t have a problem labeling their employees as essential workers to keep them producing, in many cases without substantially improving their COVID protections. Meat packing plants or prisons are great examples of this.

Because they had less savings, they couldn’t rely on them to stop working. They had to keep going to work despite the risks.

Many homes lacked a fridge or running water, forcing people to go out to get food and water daily, exposing themselves to COVID further

Because they are poorer, more people live in the same dwelling, spreading the virus inside homes when people caught it outside

Because real estate is unaffordable, their homes are smaller and with more people, forcing them to spend time outside, with neighbors who are in the same situation, further spreading the virus

Because they can’t always afford good food or going to the gym, their average health is lower, increasing their fatality rate when they did catch the virus.

Economic stimuli that didn’t go directly to the pockets of the poor frequently ended up simply pushing asset prices up, which drove a dramatic increase in stock market wealth for the richest ones, increasing the cost of most assets, and making them even more unaffordable to poorer people.

What should have been done instead is sending these people food, water, cash and medicine directly to their homes so they didn’t need to go out. This was done in Medellín, Colombia with success, for example. For those essential workers who had to work, better conditions should have been implemented earlier on. And all the stimulus should have gone directly to their pockets.

15. Missing that the Virus Would Mutate

Here’s from The Hammer and the Dance, on March 18 2020:

All the pain that has come from new variants was known a long time ago. It should have pushed countries to act more aggressively to curtail the virus. They didn’t.

14. Not Understanding Exponentials

Most countries, early on:

“Oh, we just have 10 cases this week, it’s nothing.”

“It’s just 50 cases, there’s no epidemic.”

“The entire country only has 250 cases this week! This is about to disappear.”

“1,000 cases, what’s that? Nothing. A handful of people might die this week, that’s it.”

They were lacking the perspective that, at the spreading speed, within a few weeks the entire country would be infected.

You would imagine that seeing graphs like this would have scared people, but in many cases it didn’t.

You would imagine they would have learned the lesson, but then again the same thing has happened in each wave, and every time most governments failed to react until it was too late.

Ideally, we would all develop an intuition for exponentials. Short of that, we have to admit that exponentials are counter-intuitive, so that whenever we see one, we suspend our intuition and pay attention to data.

13. Not Realizing the Value of Time has Changed

“If you need to be right before you move, you will never win.

Perfection is the enemy of good.

Speed trumps perfection.”

—Mike Ryan, WHO Director

This goes hand in hand with exponentials and was the main message of my first COVID article.

It wasn’t precise, but it was right. With an exponential, every day is more expensive (in cases, deaths, and management cost) than the next, so you need to act quickly, even with incomplete information.

This is not what people are used to. In everyday life there are no exponentials that change your life in a matter of days. We’re used to living with a pretty stable cost of time. When faced with a dilemma, it normally makes sense to wait, gather more information, and make a better decision in the future.

But with exponentials, it doesn’t work. Most politicians—and lots of people—didn’t realize this. They kept postponing decisions, while the clock was ticking ever more loudly.

12. Be Unable to Make Decisions Under Uncertainty

Back in March of last year, there were a lot of things we didn’t know:

Is this virus transmitted through fomites? (rarely)

Is it transmitted through close contact? (more through aerosols)

How much do masks help? (a lot)

Does the virus spread outdoors? (barely)

How much can a good test-trace-isolate program help? (it’s crucial)

Etc.

If you have the luxury of time, you just wait to learn these things before making decisions. But if you can’t wait, you need to make calls without all the data you’d like to have.

For example, Sweden still doesn’t recommend masks because they say they’re unproven, by which they mean there is no randomized double-blind experiment to prove masks work. Double-blind studies are, of course, the golden standard of science.

You’ll excuse me for venturing that the gold standard of science is a tall order to achieve in the middle of a pandemic. Also, how the hell are you supposed to blindly test the impact of masks? Will people not realize they wear the masks?

There was plenty of evidence for masks—including good old intuition—short of that golden standard. If decision-makers can’t make decisions with this level of uncertainty, they shouldn’t be making any decisions at all.

Another example of failure to incorporate quickly new information came with aerosol spread.

We’ve all seen videos like this one:

The moment we see something like this, we should assume there’s aerosol spread and act accordingly. When an overwhelming amount of new data appears supporting it, it’s criminal to keep denying it.

Many countries didn’t feel comfortable making decisions under uncertainty, and we all paid the price.

11. Misunderstanding Individual Freedom

“Wearing a mask is against my individual rights!”

“Vaccine passports are against the individual freedom to decide whether I want to get vaccinated or not!”

You do you. People should be free to do whatever they want—as long as they don’t affect other people. Wearing a mask or not being vaccinated, though, affects other people: you can infect others, send them to the hospital, or even kill them.

You are not free to punch somebody in the face, because other people suffer the blow. You are not free to drive without a license, because you can kill somebody else. Heck, in most US states you are not even free to drive without a seat belt, walk on the street drinking alcohol, or simply be naked in public, all of which have a much lighter impact on others than spreading the coronavirus.

Individual freedom is important. It’s not the only important thing, however. It needs to be balanced with other goals. In this case, life, economic activity, and freedom of society.

10. Making Privacy Sacred

For over a year, countries have had to balance destroying lives, the economy, freedom, and privacy.

In the US and Europe, over 1.5 million people have died. Governments have printed trillions of dollars to keep their economies afloat. Tens of millions lost their jobs. Hundreds of millions have been stuck at home. We’ve sacrificed our lives, our livelihoods, and our freedoms. But, somehow, our privacy was sacred.

Yes, that privacy that you give away five times a day when you tap the button that says “accept terms of service.” That privacy which doesn’t exist for the taxman, who knows everything about you. That privacy which doesn’t exist, because companies know more about you than you yourself know sell that information online.

Somehow, privacy prevailed.

I think it’s simply because governments didn’t want to get into that debate. Politicians were lazy, risk-averse, or both.

It’s unfortunate, because South Korea had already solved exactly how to get the best of both worlds: great contact tracing, isolations and quarantines, with a very limited reduction in privacy. As with everything else, the West ignored them.

9. Challenge Trials

You probably heard that Moderna designed its vaccine in two days, by January 13th 2020! Most of the time until approval, 11 months later, was spent testing the vaccine. Cutting that timeline would have saved trillions in the economy and millions of lives.

But is it right to allow a shorter testing period? Well, let’s go back to our infection parties from before.

A challenge trial is like an infection party, except it’s a win-win for everybody. Those who receive the vaccine get a shot at being protected from the infection instead of letting their immune system fend for itself. They get paid by the pharma companies (potentially a lot of money).

Why is this better than the current system?

It’s their decision. Why should we prevent people from doing what they want if it doesn’t have bad consequences on others? Especially if it has good consequences?!

They get compensated for their risk. Today, many jobs carry a risk of death, like mining or fishing. We don’t stop these people from working because it’s risky. We pay them.

It turns the mavericks from our infection parties into social saviors. If you want to risk yourself for others, does it make any sense to prevent that?

They’re less biased, as both the exposure (timing of infection, virus challenge dose) and outcome (assessment of blood biomarkers) are standardized.

And the most important: It’s the same as the normal vaccination trials, except much faster and controlled! In a normal trial, you wait patiently for the very same people to catch the virus from the environment instead of from the lab. Isn’t it better to do it quickly, in a controlled environment?

This is not just valid for COVID. We need to approve and regulate challenge trials for other illnesses, starting with those that are death sentences anyways.

8. Seeing Nails Everywhere

“If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail”—Abraham Maslow

Back in March 2020, with no preparation against COVID, the only thing governments could do is apply a Hammer, locking down to slow the virus and buy time.

The Hammer was not a solution to the crisis. It was a stopgap measure while governments figured how to better manage the crisis, how to dance.

But they never learned to dance applying (the measures that come afterwards to keep infections low) including the use of good fences (border controls), great test-trace-isolate, and things like good aeration and masking. The Hammer worked, they got addicted to it, and they saw nails everywhere.

So while Westerners have followed anxiously the drama of new waves of cases and vaccine rollouts, China’s economy boomed by nearly 20%. New Zealanders and Australians have been enjoying life-as-usual all this time.

7. Aerosols, Outdoors, Masks, and Superspreaders

On February 8th 2020, the Chinese published a paper suggesting aerosol spread. China’s president shared this with Trump.

On March 2020, we already knew that the biggest risk was from indoor superspreader events.

In my March 18th 2020 article “The Hammer and the Dance,”, I already recommended masks. That means there was enough evidence already by then to make the call.

On April 7th 2020, a Chinese paper had found that only 0.5% of more than 1,000 outbreak infections had happened outdoors.

We’ve had enough information to act on all of this for over a year. Japan, for example, accepted aerosol transmission on February 2020. And yet somehow this didn’t percolate into decision-making.

Yet the CDC took until April 2020 to advise masks—while Fauci said early on they would only benefit healthcare workers, knowing perfectly well that wasn’t true. They accepted aerosol transmission in October, and only fully in May 2021. The WHO recommended masks only in June 2020! As we saw before, Sweden still doesn’t.

We should have accepted early on aerosol spread, how it tends to cause superspreader events, and how good ventilation, outdoors, and masks helped as a result.

If we had done so, we could have allowed people to go out at any time.

We could have freed them from masks when nobody is around them.

We could have allowed all businesses to open if they could figure out a way to operate outdoors.

We could have invested in better ventilation. Pushed people to keep the windows open.

Every one of these decisions could have made a world of difference for people. But we didn’t, because we ignored what we learned about how this virus spreads.

6. Regionalism

Monkey see, monkey do.

I thought this was just valid for normal humans, but apparently it’s valid at the country level too. For example:

European countries: “South Korea and Taiwan have stopped the virus? Who cares! What has Italy done? What about Germany? What’s the EU saying? The US?”

US: “I don’t take lessons from anybody. Maybe let’s peek at what’s happening in Europe. Asia, you say? Why would I pay attention to Asia? They… don’t like freedom!”

The West failed. We had the solutions in front of us, and we decided not to follow them. If I had been in charge of test-trace-isolate in a Western country, for example, I would have paid millions to get some expert from Taiwan or South Korea to come advise us.

Countries like Australia or New Zealand, very much Western in culture, did pay attention to East Asian countries, maybe simply because they live close by and have stronger ties.

Iceland is far enough from Europe that it could go its own way and stop the virus. Ireland, also a low-density island in northwestern Europe, but one which is closer geographically, politically and culturally to Europe, didn’t.

There were outliers, however. Sweden decided to go against all other EU countries. They were wrong, but that independence of thought is important. Hawaii, in the US, and the Atlantic Provinces in Canada also adopted their own measures. I wish more countries and states had the courage to make their own decisions.

5. Applying Developed Country Logic to Emerging Economies

The Hammer and the Dance worked in developed economies, as South Korea, Japan, China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand, Vietnam, New Zealand, Australia, Singapore, Iceland, Hawaii, or the Atlantic Provinces proved.

Many developed economies failed at the Dance, but at least they could apply the Hammer. They did, and it worked. So they hammered the virus—and the economy—to save countless lives. That was understandable, because they had so many people at risk: older people and those with pre-existing conditions.

This cost-benefit was lopsided for emerging economies.

On one side, the cost of the Hammer was dramatically higher, because with fewer knowledge workers than in developed economies, a much higher share of the population needed to be physically present at work to be productive.

On the other side, the benefits of the Hammer were lower. Their populations tend to be younger and have fewer pre-existing conditions. Also, Hammers didn’t work as well, because emerging economies tend to have very poor, high-density cities where even Hammers don’t stop the epidemic.

Many African countries are like this, and many released their Hammers quickly. That was the right thing to do. Kenya is a good example.

But countries like India haven’t realized this dynamic. That is terrible because it meant that the country likely overshot lockdowns early on, terribly impacting the economy, but it also didn’t prepare for the new wave, which was predictable given the emergence of new, more infectious variants.

4. Not Understanding that Rapid Tests Were a Game Changer

The Cassandra of 2020 is Michael Mina. He came up with a completely new way to stop the pandemic—rapid tests—and nobody listened for months.

This was the idea: At, say, $5 a pop, you can test a big chunk of the population every day. You isolate those who test positive. The rest can go on with their lives. That quickly stomps out the epidemic, because you consistently catch most infectious people before they infect others.

Let’s take a country like the US and assume 100 million people have indoor activities with other people from outside their household any given day. If we tested them every 4 days, that’s 25 million tests a day, at a cost of ~$125 million a day. You can do that for a full year, and it only costs $45 billion. That’s around 1% of the trillions in dollars the US government is spending on stimulus, and that doesn’t even include the full economic cost of the pandemic.

Some places used it. For example, Slovakia did a country-wide, two-day campaign testing everybody, caught tens of thousands of cases, and reduced prevalence by 80%.

Meanwhile, in the US, the CDC approved the use of rapid tests—in May 2021, around 9 months after they were introduced!

Why did the CDC block their approval for so long? They were bogged down by the fact that rapid tests are less sensitive than PCR tests.

Well, of course they are. That’s how they’re so cheap and results come so fast. What they do well is not figure out whether people are infected, but infectious. They can identify a person close to the peak days of infection. If you identify and isolate people on those days, you stop the epidemic.

But the CDC didn’t understand this, didn’t approve the tests on time, didn’t make the tests their primary strategy, and condemned us to keep suffering the pandemic. The same is true of most other governments.

3. Vaccine Management

“Amateurs talk strategy. Professionals talk logistics.”

Vaccine management has been a slow-motion train crash. As soon as it became clear vaccines were our only way out of the pandemic, every single effort should have been focused on producing them, at scale, for the entire world.

We had months to prepare. And yet nearly 1.5 years after the first vaccine was discovered, supplies are still massively short worldwide.

Part of the reason was that we were way too slow to approve vaccines and agree on purchase terms with pharma companies.

Part of it has been an IP issue: Some pharma companies didn’t want to share the IP of their formulas to other companies, with ensuing conflicts.

But there’s also the problem of the transfer of technical know-how, the scarcity of weird raw materials or plastic bags, and the complexity of deal-making.

We also completely mistook what the trials proved. If a company tested two doses provided three weeks apart, then we interpreted “This is the only proven way! We MUST provide two shots in a three week interval! It’s the only proven thing!”. Instead, we should have interpreted the results:

This graph is quite easy to read. It says: 10 days after the first dose, you get most of the value. That’s why the UK correctly postponed the 2nd dose for months.

Also, the fact that three weeks works between two shots doesn’t mean that it’s better than three months, or three years. It only means “we know three weeks works’. But we have data from plenty of other vaccines to help us understand how shots can be spaced. We didn’t apply that knowledge.

All these are the type of things that projects like Warp Speed should have addressed. But governments have not been up to the task. Those failures postponed the end of the pandemic and cost trillions of dollars and millions of lives.

2. Failing at Test-Trace-Isolate

Here’s the cumulative deaths per million people so far, for a few selected countries:

As I covered in The Fail West, you can see two groups emerging here: the flat and the wavy. What makes them different?

Every single country that managed a low level of deaths was also great at tracking all cases, their contacts, and mandating and enforcing isolations and quarantines for those infected or suspected.

It makes sense: If you’re serious about controlling the epidemic, you have to bring cases down, and then identify and neutralize every single one that emerges. Otherwise, you will eventually have a new wave.

Some countries just couldn’t bring the cases low enough, no matter what they did. Argentina and Peru are good examples of this. So they didn’t even have the option to test-trace-isolate. But richer countries have no excuse.

1. Not Learning Fast Enough

At the end of the day, most of these mistakes turn around the same concept: governments and just didn’t incorporate new information fast enough.

Here’s an example of how the WHO thought about updating aerosols:

What would happen if, in your job, you learned something new, didn’t change accordingly, and when your boss came for an explanation, you said: “It was too much work to adapt”?! This is crazy!

In a normal world, incorporating new information slowly is fine. The government takes its time to analyze situations, debate solutions, and figure out a way forward that is right for most people. But we were not in normal times. We were at war. And most governments lost it because they couldn’t adapt.

This might have been fine in the second half of the 20th Century. But we’re entering a new world that is changing faster every day. Now tell me: how much confidence do you have that your governments will be able to adapt quickly enough?

I’m sure I’m missing mistakes. Which ones do you think I should add?

Get more

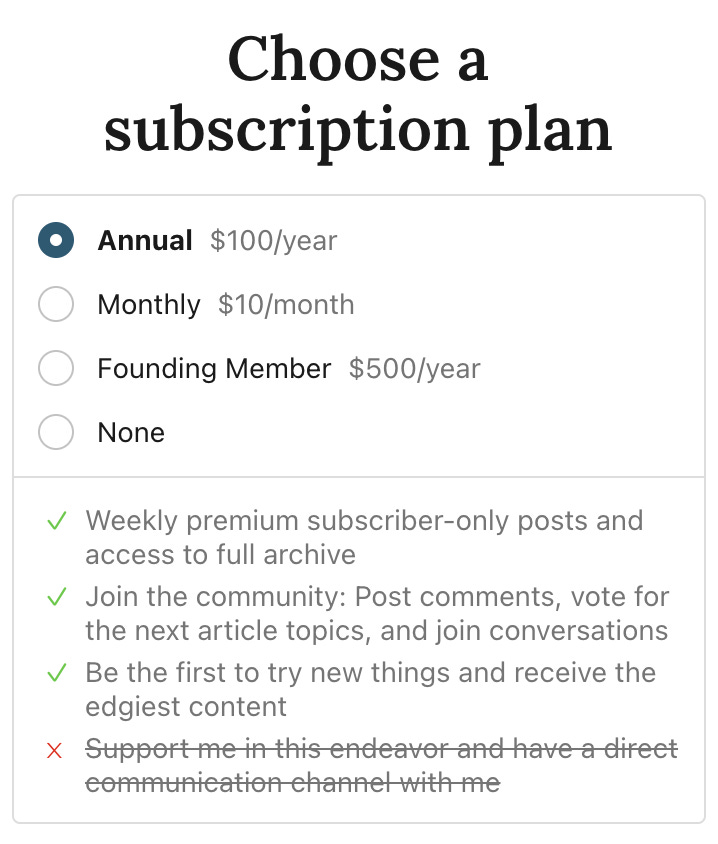

I write two articles a week. If you want to get them in your inbox weekly, please subscribe.

For the first month, both articles will be free, but after that, one will be premium. Sometimes, premium articles will dive layers deeper than the free ones, cover a different angle, add context, connect the dots, share what happens behind the scenes, uncover the underlying patterns.

Other times, as a premium subscriber you will read the edgiest, more radical, and more exploratory ideas. We will form a community where we think together about these ideas. We will have monthly conversations. In some cases, one on one. You will also be the first ones to try new things, such as launching a social currency or an NFT together. You will help me pick the next topics to explore.

How to make sure this newsletter shows up in your inbox

If this newsletter keeps showing up in his Promotions tab in Gmail, drag the emails back to the inbox. If you respond to this newsletter (or write to me at unchartedterritories@substack.com), gmail will recognize the newsletter better.

I can’t find a recent paper I read updating the cost-benefit of human challenge trials, finding that the precautionary principle is extremely costly in preventing new vaccines, and especially so for illnesses that have near certain deaths. If you know what I’m talking about, please send it to me!

Good analysis but I don't agree with items 24 and 23. My understanding is that past infection does not stop you from catching covid again (and passing it on to others). The idea of quarantined infection parties is highly impractical (people would have to be quarantined for the entire incubation and infectious period with leaks extremely difficult and expensive to avoid - eg via cleaners, hotel staff). My guess is that this would just lead to more infection in the broader community (as well as long covid if not death for a portion of participants - have you included lifelong medical costs and reduced earnings of long covid sufferers in your cost/benefit analysis?). Society has an obligation to help those who are too stupid to help themselves (eg mandatory seatbelts as you mention). And surely the people who are most concerned about their individual freedoms would not agree to be locked up in a hotel for 14+ days.

I think the biggest mistake was governments failing to realise that elimination of the virus was achievable, particularly with early action and strong fences, and failing to set this as the policy goal from the outset.

I think you missed a big thing - personalizing/politicizing decisions. Statements like "Fauci lied" lead to more such statements - "a Trump failure". These diverted and continue to divert the focus from the disease to the persons/politics. Many disastrous decisions (eg. early celebration of victory in many places) arose from political needs and such statements create more political needs. Whether the statements are true or false does not matter as much as the fact that their use makes it harder to do the thing that needs to be done - focus on the disease. Anyone who mentions an individual and attaches an emotive term to them is being human in a way that is not helpful at the moment.

As a Canadian I am particularly interested in how different the Atlantic experience was. I have heard that closing the borders was easier for them, (not being on major transport routes, relatively few crossing points), that they had better test and trace, .... I do not know how significant each of those factors was.

A consequence of disease overdispersion is that some places, especially ones with low population density, can just get lucky. If we are the lucky ones, we are sure it is due to our superiority (personalizing again). Manitoba had no first wave to speak of. They lead the country now.

We need to focus. We've had 3 pandemics in 20 years. The next one may not be so mild and a vaccine may not be so quickly forthcoming. I doubt we're even half-way through this one.